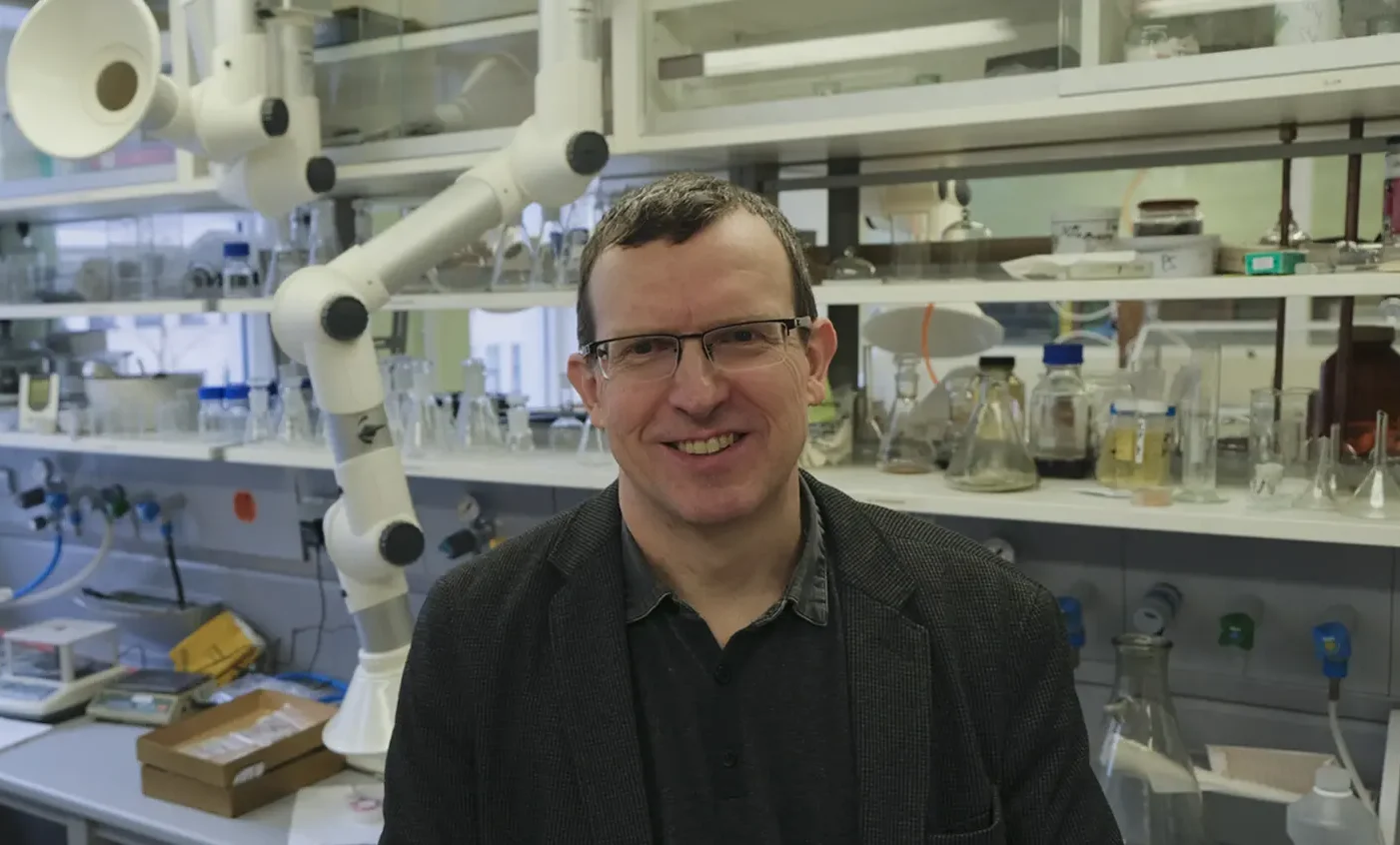

Tallinn University of Technology professor Andres Krumme. Author/source: Marek-Lars Kruusen

The production of plastic in larger quantities than wood and completely recyclable may already be within reach in Estonia.

Professor Andres Krumme lines up pieces of bioplastic film on the table in his polymer and textile technology laboratory at Tallinn University of Technology. On the surface, they are ordinary sheets of plastic, slippery and thin. Some of them have a milky tone, some are transparent. Neither the tone nor the texture betrays the connection with brittle wood. However, these bioplastics are made from wood industry residues.

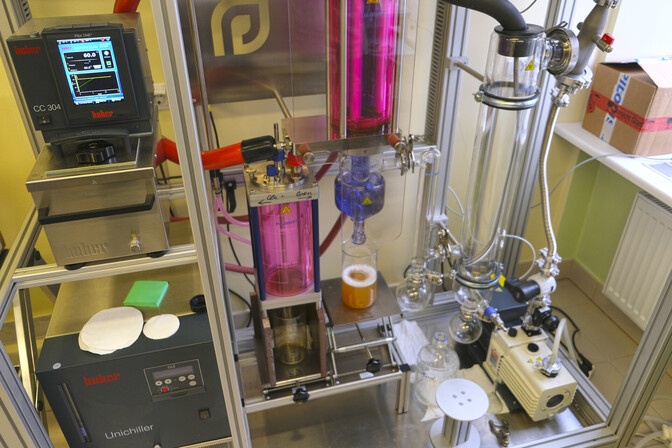

Laboratory leader Krumme's international working group dissolves the cellulose extracted from wood in an ionic liquid and then turns the plastic into a processable plastic through a chemical reaction. It melts when hot and solidifies when cool, just like regular petroleum-based plastic.

Everything here in the lab is environmentally friendly and nothing goes to waste. For example, ionic solutions can be recycled.

publicly, it takes hours to turn cellulose into bioplastic. TUT researchers invented a way to do it in just minutes. At the moment, the result can be twirled, but in the summer bioplastic will be produced in kilos with the new equipment. This is a dream towards which Krumme has been secretly moving for nearly ten years. "Our research started in 2012," he explained, "until now we did it mostly on our knees, with our own resources."

In the fall of last year, in the wind of the European Union's green revolution, the ResTA program of the Estonian Research Agency put a big idea under its shoulder and new life was breathed into the project. "This kind of opportunity is rare!" said Krumme, "We show Estonian entrepreneurs that bioplastic can be made industrially. Hopefully, this will give them more courage to create their own production in Estonia."

While oil reserves are limited, cellulose is plentiful. This most common polymer is found everywhere in nature. Cellulose is one of the basic building blocks of plant cells. According to Krumme, nature produces about 90 to 120 billion tons of it per year. By comparison, a total of about eight billion tons of plastic have been produced throughout history.

Textiles, paper, plastic can be made from cellulose. Therefore, scientists see it as a good substitute for oil, which is becoming increasingly difficult and expensive to extract.

Nordic Nokia

The Ministry of the Environment has emphasized that Estonia should value more wood itself, rather than planting it in the Nordic countries or burning it in a furnace. At the same time, petroleum-based and other plastics are brought into Estonia in heaps from other places. Therefore, the state has started to support devaluation projects.

According to Krumme, there is nothing wrong with plastic in itself. The question is how it is produced and what happens to it after use. His team would like to return the used bioplastic to the factory. This would be more environmentally friendly than single-use packaging, which is left to decompose pointlessly.

"You cannot achieve that something lasts perfectly for two weeks and then very suddenly and quickly begins to break down. Such material does not exist and will never come," said Krumme. Therefore, in his opinion, preference should be given to recyclable materials. Krumme believes that short- and medium-life wood bioplastics could even compete in price with petroleum-based plastics.

Valuing cellulose in Estonia is not a new phenomenon. The Estonian pulp industry flourished between the two world wars. After regaining independence, many factories with outdated technology were closed and interest waned. Now, packaging, hygiene products, and paper are brought to Estonia all together. Plastic arrives, for example, from Europe, Asia, North America.

However, the momentum in the Nordic countries did not slow down and they are now far ahead of us. Groups of researchers at universities and companies work on the chemistry of cellulose and other wood components. "I think this is the Nordic Nokia!" said Krumme, "Strong factories are being built. We should not just look at it from the sidelines, but should help with our competence."

Krumme has big plans in his homeland. In his opinion, there could be a bioplastic production unit at the pulp mill as well. Why not next to the forest, where the raw materials come from, and next to the packaging recycling center? Everyone would then see the circular economy in its full beauty.

This is not just empty talk. Viru Keemia Grupp, or VKG, plans to get its bioproducts factory up and running by 2027. "We have confirmed that we want to be an industrial partner for the Krumme development group," said Lauri Raid, development manager of the VKG bioproducts factory. According to him, there is a bitter race for biomaterials in the world, and wood chemistry is being especially diligently developed among the northern neighbors.

According to Raid, the crumb processing method is even more environmentally friendly than today's approaches and is suitable for the development of both bioplastics and textile fiber raw materials. This makes the Estonian solution competitive.

The market volume of the global plastic industry is nearly 370 million tons per year. According to Raid, the primary purpose of plastic based on renewable raw materials is to replace products with higher added value and to bring new bioplastic products to the market, which would initially be more suitable for a more informed consumer.

According to Kurmme, society is clearly moving towards eco products, be they domestic or from elsewhere. At the same time, the ability and interest in producing them is also growing in Estonia. According to Krumme, however, the real problem is somewhere else - weak interest in materials science among university applicants. People who care more about the environment could therefore, in addition to favoring bio-packaging, also help create practical solutions to environmental problems in the laboratory.

Source: novator.err.ee